It was during high school that I discovered the delights of the mystery genre. I enjoyed it thoroughly but generally left it feeling a little jealous of its protagonists. As an absent-minded daydreamer, my brain has always worked more like that of Anne Shirley than Sherlock Holmes or Nancy Drew. And while I loved Anne dearly, I was in awe of Nancy who was attuned to her material surroundings, focused on the facts, and so fearless that she was almost flawless — or so she appeared to my teenage self. I couldn’t help wondering whether it would be better to be less like Anne and more like Nancy. Wouldn’t that be more useful, more practical?

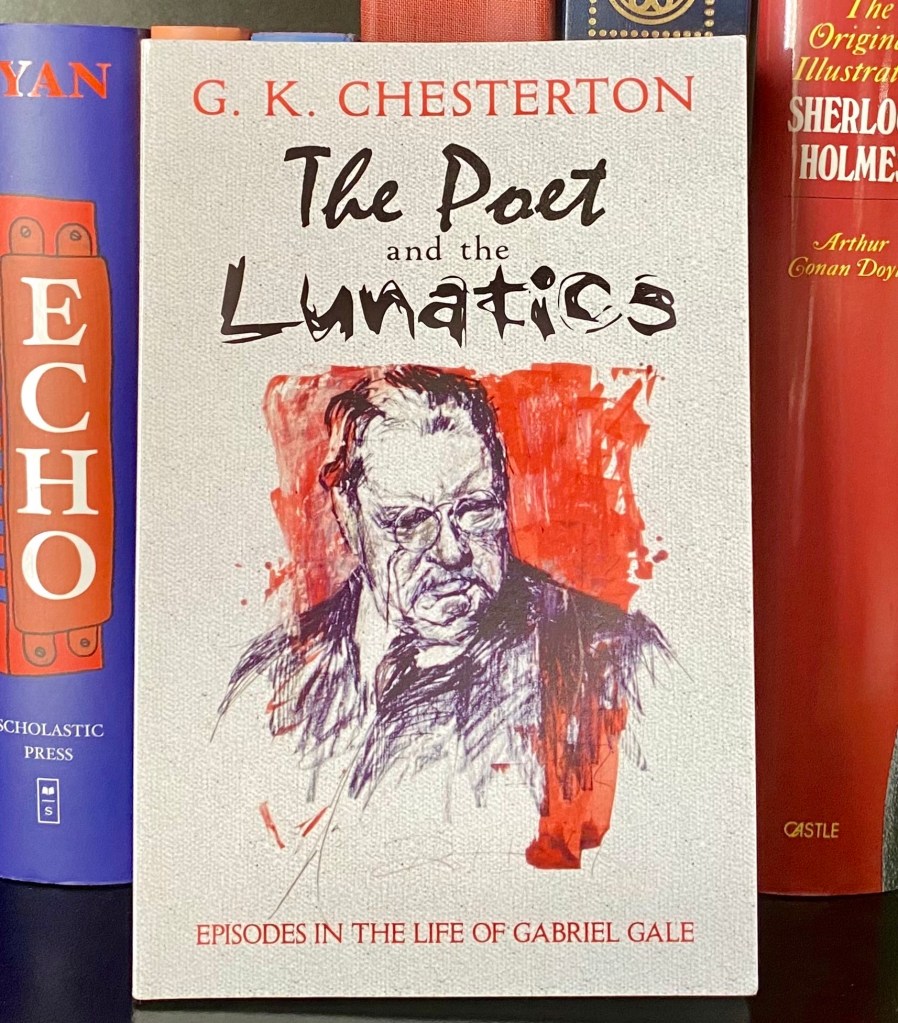

I wish that my teenage self had read The Poet and the Lunatics, a collection of mysteries by G. K. Chesterton.1 An entertaining read that also serves as a powerful case against materialism, it is characterized by the author’s fantastic plots, radical wit, and profound understanding of psychology and the Faith. For me, though, the best part of it is the protagonist Gabriel Gale.

Gale is a poet and artist who, like many others of his profession, has a tendency to procrastinate. He is usually found “loitering about . . . blowing the clocks off of dandelions,”2 discussing abstract concepts of philosophy,3 or even standing on his head. More or less useless at practical things and so eccentric as to be occasionally mistaken for a madman, he admits to having “a streak of sympathy with lunatics,”4 but he makes an important distinction:

“I am like [the lunatic] because I also can go on the wild journeys of such wild minds . . . I am unlike him because, thank God, I can generally find my way home again. The lunatic is he who loses his way and cannot return.”5

Yet it is the wild journeys of Gale’s imagination that make him capable of the rare gift of empathy. “You see,” he explains in the first story of the collection,6 “the truth is they say I have a talent for it. I generally know what they’re going to do or fancy next. I’ve known a lot of them, one way or another — religious maniacs who thought they were divine or damned . . . and revolutionary maniacs, who believed in dynamite or doing without clothes; or philosophical lunatics, of whom I could tell you some tall stories, too — men who behaved as if they lived in another world and under different stars, as I suppose they did.”

Armed with such insight, he is able to solve mysteries that baffle his more practically-minded friends, sometimes even preventing crimes before they are committed. On the scene of one such crime, Gale says:

“Look here, I want to ask you a favour, which may seem an odd one. I want you to let me question this poor chap when he comes to. Give me ten minutes alone with him, and I will promise to cure him of suicidal mania better than a policeman could.”

“But why you especially?” asked the doctor, in some natural annoyance.

“Because I am no good at practical things,” answered Gale, “and you have got beyond practical things.”7

I wonder what my teenage self would have thought of that. Perhaps I would have understood anew that God does not give useless gifts, and that the gifts of Anne and Gale serve a purpose as surely as those of Nancy and Holmes. I might have remembered that each of us is a different organ, called to a different function, and that “God arranged the organs in the body, each one of them, as he chose.”8

Notes:

- I would not have recommended it to myself before the age of 16, however, because I would not have been equipped to consider the twisted ideologies of the madmen or subject matter such as murder and suicide.

- “The Crime of Gabriel Gale”

- The stories often open with discussions on such topics as religion, the nature of freedom, or the value of art and science. At first I merely took this as a way of introducing the characters (and maybe also an excuse for Chesterton to talk about some of his favorite subjects). In fact these debates are almost always relevant to the plot, and often contain clues to the culprit’s motive. This becomes clear when Gale, like all great literary detectives, reveals his train of thought at the story’s end.

- “The Fantastic Friends”

- “The Yellow Bird”

- “The Fantastic Friends”

- “The Fantastic Friends”

- 1 Corinthians 12:18

Being a fan of Chesterton’s Father Brown series, I was excited to learn he had written other detective stories. I will definitely have to read The Poet and the Lunatics sometime soon. Thank you for sharing your discovery!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that you’ll thoroughly enjoy it!

LikeLike